*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

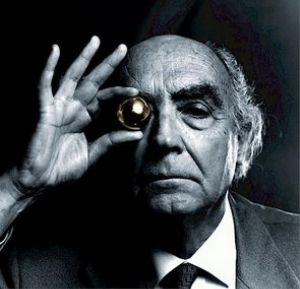

With adoration and gratitude for Jose Saramago (November16, 1922-June 18, 2010), on his birthday:

Sometimes, when I’m reading a really, really good book and I get to that part where plotlines converge or characters come together and all the emotions hit the fan, suddenly I’m sobbing out loud, blinking through tears to find out what happens next. When that happens, when I hear that horrible high-pitched, wavery whine issue from my own ugly clown mouth, I am simultaneously impressed and amazed: impressed by the author’s talent and amazed that black font on a white page could make me feel so blasted, so unhinged.

It doesn’t happen often, but when it does, I never forget.

First I should mention that I’m really not a crier. Even the sappiest ads (usually aired around Christmas or Valentine’s Day, probably because some ad exec discovered that tears make people spend more money), even those ads don’t impress me and if you look at my shelf or my queue, you won’t find any book or movie that could be characterized as a tearjerker. I’m not really drawn toward things—or people, for that matter—that want to make me cry. Why would I be? Crying is uncomfortable, messy, incapacitating, and nothing to feel proud of. Crying does not prove that my feelings are any more real or refined than the next guy’s, and tears won’t make me a better person.

Most of my favorite books made me think or laugh or dream instead of cry. I’d move south if it meant I could be closer to McCullers and Welty and Chopin and Zora Neale Hurston. I’m crazy about Toni Morrison, who could make a shopping list sound like poetry. Vladimir Nabokov makes me feel like a genius, and Ian McEwan makes me wish I could play chess better. Reading Philip K Dick makes me want to swallow some pills to see what might happen; with Ray Carver, I get thirsty for gin, and with Kesey, I want to commit myself to a nutbin, while Charlaine Harris makes me want to have sex with a dead man. With all these inspiring options, why in the world would I choose to cry?

Nevertheless, if you look at my copy of Blindess by Jose Saramago, one of my favorite books, all-time, you will find several tear-warped pages. The story is about a city hit by an epidemic of viral blindness and the chaos that ensues. Only one woman is immune and we witness the madness through her eyes. Over the course of the narrative, some really nasty things happen, as bad as you can imagine (or as bad as a spectacular storyteller who has lived, observed, and dreamed enough to see it all might imagine), and the horror ratchets up until you think you can’t take it anymore. More than once I had to put the book down and back out of the room, go pet my cat or take a hot shower or pull a swig of something strong straight from the bottle, before I could go on.

But if it was just a nauseating portrait of society’s sins, I never would have finished. But while things go from bad to rotten, some of the characters’ beauty, kindness and dignity expand, offering a counterpoint to the nihilism. Some bad people commit acts of grace and some good guys fall apart under pressure and Saramago reserves judgment. He is an omniscient Buddha, a jolly old elf—he knows precisely who’s been bad and good, but still, he’s not crossing anyone’s name off the list quite yet. There’s something very big about his perspective that I find quite comforting-the illusion of an unblinking eye in the sky who’s seen it all before and will see it all again.

I probably enjoy a mixture of acute awareness and magnanimity in my narrator for the same reason I like to believe that judges really do listen to the very end before making any decisions and why, in school, I liked the teachers who liked me, but I loved the ones who recognized every student’s uniqueness and who seemed to like everyone. When I read the newspaper, the op-eds are fun but a carefully researched, in-depth, unbiased report will always feel like the real thing. My closest friends are the ones who see all my defects and still think I’m great, and after twenty years of seeing me first thing in the morning, my husband says he’d marry me all over again.

It’s the opposite of blind faith; it’s an intimate appreciation, and it’s what really gets me.

The scene in Blindness I remember most vividly came near the end, when three women we have followed since the start of the epidemic (through filth, terror, and deprivation) finally find a safe haven and get to take a shower. It starts to rain and they take off their clothes and go out on the rooftop. Suddenly, they feel worried about what they look like, which seems rather silly considering what they’ve been through and the fact that no one can see them, but it rings true, too, because old habits die hard and because at this point, everyone—characters and readers alike—is starving for a little beauty. The two younger blind women want to know what they look like: the older woman who can see tells them they are beautiful, far more beautiful than she, but one of the blind women assures her, “You were never more beautiful,” and Saramago goes off on a riff:

Words are like that, they deceive, they pile up, it seems they do not know where to go, […] sometimes the nerves that cannot bear it any longer, they put up with a great deal, they put up with everything, it was as if they were wearing armour, we might say. The doctor’s wife has nerves of steel, and yet the doctor’s wife is reduced to tears because of a personal pronoun, an adverb, a verb, an adjective, mere grammatical categories, mere labels, just like the two women, the others, indefinite pronouns, they too are crying, they embrace the woman of the whole sentence, three graces beneath the falling rain.

As they all cry and hug, and the scene is awash in beauty and gratitude and grace, and it feels like all the ugliness in the world is cleansed and love will prevail. Even rereading this passage out of context makes me teary.

I guess I’m crying partly because I want to do that, too. I want to write a scene that could make a grown woman cry. Now that I’ve finished my second novel and realize that neither of them turned out quite as well as I’d hoped, I’m ready to try to learn a thing or two from writers like Saramago. Because face it: sooner or later, probably when my youngest starts kindergarten, I’m going to have to get a job. I can’t just sit around cooking and cleaning house forever, can I? Unless I get paid for my writing, I’m only amusing myself (and perhaps a handful of lovely friends), so I might as well use the time I have left to do a little market research just like those tear-jerking, money-grubbing advertisers did. If I want to write something commercially viable, I’ll need to discover the secret. So even though it feels a bit callous and reductionistic to dissect something so lovely, I’ve gotta get serious: What makes Saramago so effective? What can I borrow from him?

Perhaps it has something to do with the characters’ vulnerability. When people need something, we want to rise to the occasion, like for those Christian ads they run during the holidays, the ones with big-eyed baby skeletons covered with flies looking desperately into your living room: the bigger the eye-to-face ratio, the larger the impact, it seems. Crying might also help because the sight of tears probably triggers the empathetic release of some fabulous neurochemical cocktail. Also, in Saramago’s scene, the women’s nakedness definitely augments the pathos. (Mental note: More naked people; bigger eyes.)

It must also help to have a narrator who sounds like Saramago’s, one with such a hypnotic voice. His rooftop scene inhabits one paragraph of his book, one paragraph that stretches for almost five pages without pausing for much punctuation. His narrator croons like an old lover; he teases and chides but he also seems like he’s deeply in love with his characters. He’s like a horse whisperer, except he’s taming my cynicism. (Go to Wikipedia; look up hypnosis, empathy, and rhetorical devices.)

Then there’s the requisite element of surprise; either the reader or a main character should be completely astonished by a sudden turn of events. Remember in Pulp Fiction? When the kid in the back seat got shot? I was so surprised that my heart felt bruised from banging against my ribs. Many popular filmmakers are savvy to the element of surprise; they use it so much that by the end of the film you feel whipped and whiplashed. After movies like that I walk out through the theater lobby with my chest puffed out, giving fellow moviegoers a macho nod that says, Nah, it didn’t hurt that bad. I could take it! But Saramago showed me that the surprise doesn’t have to be violent—it can be a simple thing, like rain, and if it ties into the character’s greatest need (for a bath, a friend, a safe place to exist) and is expressed with tenderness, then you’ve discovered how to reach into my chest, grip my heart, pull it out my throat, take a big bite, and leave me scarred forever, nevermind if that’s not anatomically possible because it’s exactly how it feels. (Remember: Surprise+Need+Emotion=Wow.)

I want to make you cry—the good kind of cry—not because I value emotions over ideas, but because I don’t know how to do that kind of thing quite yet. In my writing, the places where my own bias and criticism show through are the places where I suspect I need to grow. Even in this essay, I can’t seem to resist a little sarcasm. My narratorial voice is still a teenager—sophomoric, eye-rolling, mired in the moment, overly concerned with appearances, worried about what you think, and prone to fits of giggles. Hopefully she’ll grow up some day—I’m waiting as patiently as I can—and in the meantime, it’s my job to point her in the right direction.

As a writer, I am a like a blind person fumbling in darkness, hoping that some seeing person will lend me a hand. So I read Saramago (or Michael Cunningham or Nicole Krauss or Marilynn Robinson) and cry. And when I cry, I feel just a little bit proud of myself for understanding, and just a tad virtuous for allowing myself to be swayed. Even though it’s illogical, when I cry, I imagine my tears are teaching me how to be a better person.

Questions: In terms of literature, who or what makes you cry? What written moments have stayed with you over the years?

Questions: In terms of literature, who or what makes you cry? What written moments have stayed with you over the years?

“The Bluest Eye” made me feel as if I would die. There are moments in there that reach out like knives.

I don’t think it’s illogical to imagine that tears have something to teach you. When any work of art honestly brings me to tears, I feel different than I do when I’m hurt and crying. I feel as though I’ve been pried open a little more, and something of value has slipped in, not necessarily something in the work itself, but something born out of my reaction to it. Even though I can’t recall each one, I feel them in here somewhere, affecting my life and my own work.

YES! The Bluest Eye. That book kills me. I taught it to my Freshman students for many years (and Sula, and Beloved- they all KILL ME.)

Beautifully put, Sparks- your comment almost made me cry!

Saramago is the author of one of my favorite novels, The Year of the Death of Ricardo Reis, a book that affected me both as a reader and a writer. I’ve encountered few authors who share his ability to see so deeply inside his characters, and understand what it is like to be a thinking person in a world in which others seem to be automatons programmed for self-interest, and where it is difficult, if not impossible, for us to see past that illusion and connect to each other.

I had no idea it was his birthday-here’s to his memory.

So true- I can’t think of many other writers who have his kind of steady emotional wisdom. He was a truly remarkable writer. Thank you for your comment!

Now I gotta read this book.

Do! You won’t be disappointed! (But avoid the movie, it just sucked.)

It’s sad and it violates my cardinal rule of books, movies or TV, that you (the writer) are the God of that story and you don’t ever have a child be hurt or die in the story, but N. Scott Momaday’s “House Made of Dawn” has a passage about two-thirds of the way in-I call it “Milly’s soliloquoy”. It starts with “I was a dirty child with yellow hair and thin little arms and legs that were big at the joints…” From her daddy, who was “turning to stone” as he moved up and down the rows, trying to grow crops in the land he came to hate, from his “deep desperate kind of love” for Milly that had “no laughter to it at all”, to her daughter’s illness being so etched into her, that she saw all her “fear and helplessness” in the face of a man she ran into, to her little Carrie laying there dying and seeming “not afraid but curious, strangely thoughtful and wise”, and the rest, it is just one of the most moving passages I’ve ever read. And infinitely desperate and sad. And I never would have heard about it had I not been lazy and taken the easy way out of college, which for me was English and not frickin’ science or econ or math.

To misquote Whitney Houston: “WordPress is wack”. I wasn’t getting emails of your new postings, or of Thypolar’s, so I checked my settings and only those two were now unchecked for some reason. So, “congrats”, I’m now subscribed to your blog, that I’ve been subscribed to since, forever it seems.

I, also, must read this book. I already need to quit my job to keep up with the blogs I like and the unread books on my shelves. Thanks.

I wonder about your cardinal rule. So many fabulous stories would never have happened if we held ourselves up to lofty ideals. Lolita is one of my all-time favorite books because it is told by a degenerate ass. (House Made of Dawn sounds wonderful- I’ll have to find a copy.)

That’s true; a lot of great books would have never been written if we were afraid to write things that made us or others squeamish. It’s something I got from my mom; she couldn’t abide anything where kids were in danger. I don’t much care to try to convince others that a book or author is great, except to say that I liked it, but, yeah, I hope you like that book if you try it. I can’t remember how I reacted when I first read that speech of Milly’s, but she talks about going to work in a city, meeting a man, having a baby, then he left her, but her time with Carrie was all that she needed then. Then the next paragraph starts with “And Carrie was four.” And you know right then that it’s going to be so sad, you just get that feeling, but you can’t help but reading. I don’t know if I want to write anything that sad, but something that powerful, yes, that would feel great.

I’m embarrassed to say I’d never heard of Jose Saramago. Can I blame living out in the woods? I’ve added this book to my library requests. So many powerful things to ponder here and there just isn’t space in a reply to touch on them all. One thing that comes to mind is asking if you have read Priscilla Long’s book, ‘The Writer’s Portable Mentor’. She talks about the music of words, the tones associated with vowels, and how most poets know how to use that music to bring out emotional responses but writers neglect it. We recognize that lyrical writing, but we don’t always know how or why it pulls at our emotions.Unless we sit down and analyze the sounds and structure, like you are doing here. And I hear that same music in your writing; a lot of this post reads to me like poetry. I rarely cry, too. My husband is the one who cries watching movies (he always tears up watching ‘Dead Poet’s Society’) but I don’t. Only twice have I cried, and both times were movies, not books, even though I don’t watch that many movies. ‘Smoke Signals’ gets me every time. Some try to bill that movie as a comedy, which it is not. At the end a poem is read during a fly-over of the Snake River. The poem is called ‘Forgiving our Fathers’. I cry. The second time I’ve cried at a movie should make you laugh, ‘Prancer’. At the very end, when magic still exists and there’s still something to believe in. The flip side is that there are two authors who make me laugh out loud. Cornelia Read and Meg Gardiner. The way they turn the language is great. Fantastic post.

Absolutely blame the woods- he’s a rather obscure writer known to few, even though he won a Nobel prize. Can’t remember if he was Portuguese and wrote in Spanish or the other way around but you say his name with a hard “J.” I haven’t read all his books, but the ones I’ve read are spectacular, sort of the way Italo Calvino is spectacular- cerebral, lyrical, and magical. He died a few years ago. Thank you for your kind words-I’m ashamed to say I haven’t seen Smoke Signals although smart people have been telling me to for years. I gotta see that!

Beautiful essay, Anna. I haven’t read the book but you certainly made me add it to my TBR list.

For me, the books that move me most deeply are the ones in which the author’s restraint allows me room to invest my own emotions in the characters. If the character cries, I don’t need to. If the character should cry and doesn’t, I will do it for her. This is what I’m trying to accomplish when I write, but I have a lot to learn before I can make that happen.

I never thought about it that away, Averil, but I think you just nutshelled it. The suppressed emotion is fully experienced by the reader. Hmmmm, I’ll have to mull that over…

I can’t remember the last time I lost it completely at a book - besides the time, recently, that Jamrach’s Menagerie caused me to faint…too many disappointments in my reading supply recently. I’ll have to try Blindness if my library has it, something that will hopefully get through to me as it did so well to you.

A case of Stendahl’s Syndrome? I’ve always wanted to feel that!

Ah! No, I am not quite so cultured as to faint from beauty, sadly enough. It was because I am terribly squeamish, and the book started to get progressively grimmer. I’m more of a Victorian lady, all in a swoon over nothing.

Ha! I’m picturing too-tight corsets and fainting couches. I think perhaps you should avoid Blindness, I’m afraid it might make you swoony.

It’s interesting. I am a crier; I cry at everything, commercials and human-interest news stories (puppy saved his owner? BAWL!); even third-hand thoughts still have the power to draw tears. (Sometimes I think it’s too bad I have no acting ability. It would be so nice to use my sob-ability in a role.) So, of all the things a writer can do to impress me, drawing (my) tears doesn’t rank as high as other things.

I will say that The Time Traveler’s Wife rendered me almost incapable of doing anything but cry… for at least two days. It affected me so much, I can’t even tell you if it’s a good book (Erik thinks it’s “emotionally manipulative.”), but it’s one of the inspirations for that piece I wrote for Litcrawl.

As for what does make me bow down to a writer… it’s hard for me to untangle “so-and-so is a good writer” from “I LOVED this story and its characters.” I mean, I think I know good writing when I see it, but if I don’t connect to the story, the writing won’t save it for me, and I adore (and reread) plenty of books with only average-quality writing. It makes me wonder if perhaps, in my own art, I’m not as much of a craft person as I am… something else, but what? It’s a question I’d like to be able to answer someday.

I’m with Erik- I don’t like the tears to be jerked out with a sharp tool. You bring up a good point- I’m not sure if crying is a requisite for good writing, but feeling something might be, for me. I’ll go read your piece now…

Pingback: Open Mic Friday! you talk: what makes a book good? | the Satsumabug blog